(A few of my notes on the story, to be read before or after you read it.)

The Story of Mimi-Nashi-Hōichi

By Lafcadio Hearn

More than seven hundred years ago, at Dan-no-ura, in the Straits of Shimonoséki, was fought the last battle of the long contest between the Heiké, or Taira clan, and the Genji, or Minamoto clan.1 There the Heiké perished utterly, with their women and children, and their infant emperor likewise—now remembered as Antoku Tennō.2 And that sea and shore have been haunted for seven hundred years. Elsewhere I told you about the strange crabs found there, called Heiké crabs, which have human faces on their backs, and are said to be the spirits of the Heiké warriors.3 But there are many strange things to be seen and heard along that coast. On dark nights thousands of ghostly fires hover about the beach, or flit above the waves—pale lights which the fishermen call Oni-bi, or demon-fires—and, whenever the winds are up, a sound of great shouting comes from that sea, like a clamor of battle.4

In former years the Heiké were much more restless than they now are. They would rise about ships passing in the night, and try to sink them; and at all times they would watch for swimmers, to pull them down. It was in order to appease those dead that the Buddhist temple, Amidaji, was built at Akamagaséki.5 A cemetery also was made close by, near the beach; and within it were set up monuments inscribed with the names of the drowned emperor and of his great vassals; and Buddhist services were regularly performed there, on behalf of the spirits of them. After the temple had been built, and the tombs erected, the Heiké gave less trouble than before; but they continued to do queer things at intervals, proving that they had not found the perfect peace.

Some centuries ago there lived at Akamagaséki a blind man named Hōichi, who was famed for his skill in recitation and in playing upon the biwa.6 From childhood he had been trained to recite and to play; and while yet a lad he had surpassed his teachers. As a professional biwa-hōshi he became famous chiefly by his recitations of the history of the Heiké and the Genji; and it is said that when he sang the song of the battle of Dan-no-ura “even the goblins [kijin] could not refrain from tears.”7

At the outset of his career, Hōichi was very poor; but he found a good friend to help him. The priest of the Amidaji was fond of poetry and music; and he often invited Hōichi to the temple, to play and recite. Afterwards, being much impressed by the wonderful skill of the lad, the priest proposed that Hōichi should make the temple his home; and this offer was gratefully accepted. Hōichi was given a room in the temple-building; and, in return for food and lodging, he was required only to gratify the priest with a musical performance on certain evenings, when otherwise disengaged.

One summer night the priest was called away, to perform a Buddhist service at the house of a dead parishioner; and he went there with his acolyte, leaving Hōichi alone in the temple. It was a hot night; and the blind man sought to cool himself on the verandah before his sleeping-room. The verandah overlooked a small garden in the rear of the Amidaji. There Hōichi waited for the priest’s return, and tried to relieve his solitude by practicing upon his biwa. Midnight passed; and the priest did not appear. But the atmosphere was still too warm for comfort within doors; and Hōichi remained outside. At last he heard steps approaching from the back gate. Somebody crossed the garden, advanced to the verandah, and halted directly in front of him—but it was not the priest. A deep voice called the blind man’s name—abruptly and unceremoniously, in the manner of a samurai summoning an inferior:

“Hōichi!”

Hōichi was too much startled, for the moment, to respond; and the voice called again, in a tone of harsh command:

“Hōichi!”

“Hai!”8 answered the blind man, frightened by the menace in the voice. “I am blind—I cannot know who calls!”

“There is nothing to fear,” the stranger exclaimed, speaking more gently. “I am stopping near this temple, and have been sent to you with a message. My present lord, a person of exceedingly high rank, is now staying in Akamagaséki, with many noble attendants. He wished to view the scene of the battle of Dan-no-ura; and today he visited that place. Having heard of your skill in reciting the story of the battle, he now desires to hear your performance: so you will take your biwa and come with me at once to the house where the august assembly is waiting.”

In those times, the order of a samurai was not to be lightly disobeyed. Hōichi donned his sandals, took his biwa, and went away with the stranger, who guided him deftly, but obliged him to walk very fast. The hand that guided was iron; and the clank of the warrior’s stride proved him fully armed—probably some palace-guard on duty. Hōichi’s first alarm was over: he began to imagine himself in good luck—for, remembering the retainer’s assurance about a “person of exceedingly high rank,” he thought that the lord who wished to hear the recitation could not be less than a daimyō of the first class.9 Presently the samurai halted; and Hōichi became aware that they had arrived at a large gateway; and he wondered, for he could not remember any large gate in that part of the town, except the main gate of the Amidaji. “Kaimon!”10 the samurai called, and there was a sound of unbarring; and the twain passed on. They traversed a space of garden, and halted again before some entrance; and the retainer cried in a loud voice, “Within there! I have brought Hōichi.” Then came sounds of feet hurrying, and screens sliding, and rain-doors opening, and voices of women in converse. By the language of the women Hōichi knew them to be domestics in some noble household; but he could not imagine to what place he had been conducted. Little time was allowed him for conjecture. After he had been helped to mount several stone steps, upon the last of which he was told to leave his sandals, a woman’s hand guided him along interminable reaches of polished planking, and round pillared angles too many to remember, and over widths amazing of matted floor, into the middle of some vast apartment. There he thought that many great people were assembled: the sound of the rustling of silk was like the sound of leaves in a forest. He heard also a great humming of voices, talking in undertones; and the speech was the speech of courts.

Hōichi was told to put himself at ease, and he found a kneeling-cushion ready for him. After having taken his place upon it, and tuned his instrument, the voice of a woman—whom he divined to be the Rōjo, or matron in charge of the female service—addressed him, saying:

“It is now required that the history of the Heiké be recited, to the accompaniment of the biwa.”

Now the entire recital would have required a time of many nights: therefore Hōichi ventured a question:

“As the whole of the story is not soon told, what portion is it augustly desired that I now recite?”

The woman’s voice made answer:

“Recite the story of the battle at Dan-no-ura, for the pity of it is the most deep.”11

Then Hōichi lifted up his voice, and chanted the chant of the fight on the bitter sea—wonderfully making his biwa to sound like the straining of oars and the rushing of ships, the whirr and the hissing of arrows, the shouting and trampling of men, the crashing of steel upon helmets, the plunging of slain in the flood. And to left and right of him, in the pauses of his playing, he could hear voices murmuring praise: “How marvelous an artist!”—“Never in our own province was playing heard like this!”—“Not in all the empire is there another singer like Hōichi!” Then fresh courage came to him, and he played and sang yet better than before; and a hush of wonder deepened about him. But when at last he came to tell the fate of the fair and helpless—the piteous perishing of the women and children, and the death-leap of Nii-no-Ama,12 with the imperial infant in her arms—then all the listeners uttered together one long, long shuddering cry of anguish; and thereafter they wept and wailed so loudly and so wildly that the blind man was frightened by the violence and grief that he had made. For much time the sobbing and the wailing continued. But gradually the sounds of lamentation died away; and again, in the great stillness that followed, Hōichi heard the voice of the woman whom he supposed to be the Rōjo.13

She said:

“Although we had been assured that you were a very skillful player upon the biwa, and without an equal in recitative, we did not know that any one could be so skillful as you have proved yourself tonight. Our lord has been pleased to say that he intends to bestow upon you a fitting reward. But he desires that you shall perform before him once every night for the next six nights—after which time he will probably make his august return-journey. Tomorrow night, therefore, you are to come here at the same hour. The retainer who tonight conducted you will be sent for you. There is another matter about which I have been ordered to inform you. It is required that you shall speak to no one of your visits here, during the time of our lord’s august sojourn at Akamagaséki. As he is traveling incognito,14 he commands that no mention of these things be made. You are now free to go back to your temple.”

After Hōichi had duly expressed his thanks, a woman’s hand conducted him to the entrance of the house, where the same retainer, who had before guided him, was waiting to take him home. The retainer led him to the verandah at the rear of the temple, and there bade him farewell.

It was almost dawn when Hōichi returned; but his absence from the temple had not been observed—as the priest, coming back at a very late hour, had supposed him asleep. During the day Hōichi was able to take some rest; and he said nothing about his strange adventure. In the middle of the following night the samurai again came for him, and led him to the august assembly, where he gave another recitation with the same success that had attended his previous performance. But during this second visit his absence from the temple was accidentally discovered; and after his return in the morning he was summoned to the presence of the priest, who said to him, in a tone of kindly reproach:

“We have been very anxious about you, friend Hōichi. To go out, blind and alone, at so late an hour, is dangerous. Why did you go without telling us? I could have ordered a servant to accompany you. And where have you been?”

Hōichi answered, evasively:

“Pardon me, kind friend! I had to attend to some private business; and I could not arrange the matter at any other hour.”

The priest was surprised, rather than pained, by Hōichi’s reticence: he felt it to be unnatural, and suspected something wrong. He feared that the blind lad had been bewitched or deluded by some evil spirits. He did not ask any more questions; but he privately instructed the men-servants of the temple to keep watch upon Hōichi’s movements, and to follow him in case that he should again leave the temple after dark.

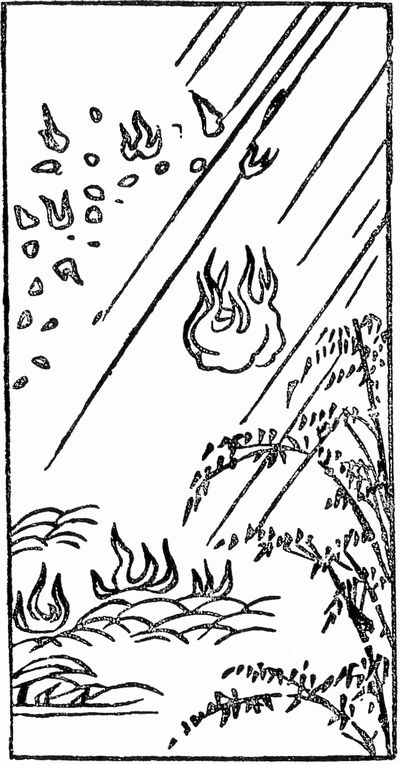

On the very next night, Hōichi was seen to leave the temple; and the servants immediately lighted their lanterns, and followed after him. But it was a rainy night, and very dark; and before the temple-folks could get to the roadway, Hōichi had disappeared. Evidently he had walked very fast—a strange thing, considering his blindness; for the road was in a bad condition. The men hurried through the streets, making inquiries at every house which Hōichi was accustomed to visit; but nobody could give them any news of him. At last, as they were returning to the temple by way of the shore, they were startled by the sound of a biwa, furiously played, in the cemetery of the Amidaji. Except for some ghostly fires—such as usually flitted there on dark nights—all was blackness in that direction. But the men at once hastened to the cemetery; and there, by the help of their lanterns, they discovered Hōichi—sitting alone in the rain before the memorial tomb of Antoku Tennō,15 making his biwa resound, and loudly chanting the chant of the battle of Dan-no-ura. And behind him, and about him, and everywhere above the tombs, the fires of the dead were burning, like candles. Never before had so great a host of Oni-bi appeared in the sight of mortal man.

“Hōichi San! Hōichi San!” the servants cried, “you are bewitched! Hōichi San!”

But the blind man did not seem to hear. Strenuously he made his biwa to rattle and ring and clang; more and more wildly he chanted the chant of the battle of Dan-no-ura. They caught hold of him; they shouted into his ear:

“Hōichi San! Hōichi San! Come home with us at once!”

Reprovingly he spoke to them:

“To interrupt me in such a manner, before this august assembly, will not be tolerated.”

Whereat, in spite of the weirdness of the thing, the servants could not help laughing. Sure that he had been bewitched, they now seized him, and pulled him up on his feet, and by main force hurried him back to the temple, where he was immediately relieved of his wet clothes, by order of the priest. Then the priest insisted upon a full explanation of his friend’s astonishing behavior.

Hōichi long hesitated to speak. But at last, finding that his conduct had really alarmed and angered the good priest, he decided to abandon his reserve; and he related everything that had happened from the time of first visit of the samurai.

The priest said:

“Hōichi, my poor friend, you are now in great danger! How unfortunate that you did not tell me all this before! Your wonderful skill in music has indeed brought you into strange trouble. By this time you must be aware that you have not been visiting any house whatever, but have been passing your nights in the cemetery, among the tombs of the Heiké—and it was before the memorial-tomb of Antoku Tennō that our people tonight found you, sitting in the rain. All that you have been imagining was illusion—except the calling of the dead. By once obeying them, you have put yourself in their power. If you obey them again, after what has already occurred, they will tear you in pieces. But they would have destroyed you, sooner or later, in any event. Now I shall not be able to remain with you tonight: I am called away to perform another service. But, before I go, it will be necessary to protect your body by writing holy texts upon it.”

Before sundown the priest and his acolyte stripped Hōichi: then, with their writing-brushes, they traced upon his breast and back, head and face and neck, limbs and hands and feet—even upon the soles of his feet, and upon all parts of his body—the text of the holy sūtra called Hannya-Shin-Kyō.16 When this had been done, the priest instructed Hōichi, saying:

“Tonight, as soon as I go away, you must seat yourself on the verandah, and wait. You will be called. But, whatever may happen, do not answer, and do not move. Say nothing and sit still—as if meditating. If you stir, or make any noise, you will be torn asunder. Do not get frightened; and do not think of calling for help—because no help could save you. If you do exactly as I tell you, the danger will pass, and you will have nothing more to fear.”

After dark the priest and the acolyte went away; and Hōichi seated himself on the verandah, according to the instructions given him. He laid his biwa on the planking beside him, and, assuming the attitude of meditation, remained quite still, taking care not to cough, or to breathe audibly. For hours he stayed thus.

Then, from the roadway, he heard the steps coming. They passed the gate, crossed the garden, approached the verandah, stopped—directly in front of him.

“Hōichi!” the deep voice called. But the blind man held his breath, and sat motionless.

“Hōichi!” grimly called the voice a second time. Then a third time—savagely:

“Hōichi!”

Hōichi remained as still as a stone—and the voice grumbled:

“No answer! That won’t do! Must see where the fellow is.”

There was a noise of heavy feet mounting upon the verandah. The feet approached deliberately—halted beside him. Then, for long minutes—during which Hōichi felt his whole body shake to the beating of his heart—there was dead silence.

At last the gruff voice muttered close to him:

“Here is the biwa; but of the biwa-player I see—only two ears! So that explains why he did not answer: he had no mouth to answer with—there is nothing left of him but his ears. Now to my lord those ears I will take—in proof that the august commands have been obeyed, so far as was possible.”

At that instant Hōichi felt his ears gripped by fingers of iron, and torn off! Great as the pain was, he gave no cry. The heavy footfalls receded along the verandah—descended into the garden—passed out to the roadway—ceased. From either side of his head, the blind man felt a thick warm trickling; but he dared not lift his hands.

Before sunrise the priest came back. He hastened at once to the verandah in the rear, stepped and slipped upon something clammy, and uttered a cry of horror—for he saw, by the light of his lantern, that the clamminess was blood. But he perceived Hōichi sitting there, in the attitude of meditation—with the blood still oozing from his wounds.

“My poor Hōichi!” cried the startled priest, “What is this? You have been hurt?”

At the sound of his friend’s voice, the blind man felt safe. He burst out sobbing, and tearfully told his adventure of the night.

“Poor, poor Hōichi!” the priest exclaimed, “All my fault—my very grievous fault! Everywhere upon your body the holy texts had been written—except upon your ears! I trusted my acolyte to do that part of the work; and it was very, very wrong of me not to have made sure that he had done it! Well, the matter cannot now be helped—we can only try to heal your hurts as soon as possible. Cheer up, friend! The danger is now well over. You will never again be troubled by those visitors.”

With the aid of a good doctor, Hōichi soon recovered from his injuries. The story of his strange adventure spread far and wide, and soon made him famous. Many noble persons went to Akamagaséki to hear him recite; and large presents of money were given to him, so that he became a wealthy man. But from the time of his adventure, he was known only by the appellation of Mimi-nashi-Hōichi: “Hōichi-the-Earless.”

-

The characters of the Taira clan (平家) can be read as Heiké using their Chinese reading. Similarily, the characters for the Minamoto clan (源氏) can be read Genji using their Chinese reading. For the Taira in particular it was common to use the Chinese reading of their name. I’m unsure why. Perhaps it’s because Chinese was the language of the aristocrats at the time when the Taira controlled things. At any rate, long story short: Heiké/Taira refer to the same family, and Minamoto/Genji also refer to the same family. ↩

-

The war between the Heiké and the Genji is the single most famous war in Japanese history: the Genpei War, the struggle between the Taira (Heiké) and Minamoto (Genji) clans for control of Japan. The war is famously recounted in the classic Japanese epic, 平家物語 Heike Monogatari—The Tale of Heike. The war marks the end of the classical period of Japanese history and the beginning of the shogun and samurai rule.

Briefly: Before the rise of the shogun, various families controlled the emperor and ran things in his name. Two of these families were the Minamoto and the Taira, both offshoots of the powerful Fujiwara family. As these things go, they didn’t like each other very much. Long story short, the Taira rose to power in 1161 by defeating the Minamoto. They managed to fend off attempts by the Minamoto to regain control and began a series of moves intended to eliminate all rivals—Godfather-style. In 1180, the head of the Taira, Taira no Kiyomori, put his grandson—Antoku Tennō (Emperor Antoku)—on the throne. This action provoked the former emperor’s son to send a call to arms to the Minamoto. Thus began the Genpei War. The war lasted 5 years from 1180 to 1185 and culminated with the battle of Dan-no-ura, the most famous naval battle in Japanese history. In this battle the Taira had the advantage at first but the tides (literally) shifted and the advantage then went to the Minamoto. A defection of a Taira general who revealed the location of Emperor Antoku sealed the Taira defeat. Many of the Taira samurai threw themselves into the ocean rather than surrender, including Emperor Antoku and his grandmother Lady Tokiko.

With the Taira clan destroyed, the Minamoto soon established the Kamakura shogunate, marking the beginning of military rule of the country. The samurai would go on to control Japan for over 650 years until the Meiji Restoration in 1868.

You can read all about the story on the Internet and I recommend you do—it’s a great story! It has been translated many times, but if you are really interested, I suggest finding the translation of Eiji Yoshikawa’s amazing retelling of the story, titled The Heike Story. Here is a copy on Amazon. ↩

-

Hearn wrote: See my Kottō, for a description of these curious crabs.

My comment: He is referring to another text which is was originally included in the same volume as this story. We don’t have that to cross-reference, so I’ll jump in with my own description.

Heiké crabs, or Heikégani, is a species of Japanese crabs with a shell that looks eerily like an angry face.

Strange, eh? In Kottō, Hearn tells us that a common Japanese myth says these crabs are reincarnations of the defeated Heiké warriors. Even today, many believe this. However, Carl Sagan gave a more scientific view. He hypothesized that these crabs are an example of artificial selection. According to his idea, crabs with shells resembling faces were thrown back to sea by fishermen out of respect for the Heiké warriors, while those without faces were eaten; since the survival rate for crabs with faces were much higher than others, over the centuries crabs with faces started to be much more common that those without faces. ↩

-

Oni-bi (鬼火) are floating flames, usually blue but occasionally red or yellow, as small as a candle flame or as large as a human. They usually gather together in groups of 20–30, and they eat the souls of any humans foolish enough to approach them. They are said to be born from the corpses of resentful humans and animals. They are similar to will-o’-wisps, if you are familiar with European folklore. ↩

-

Hearn wrote: Or, Shimonoséki. The town is also known by the name of Bakkan.

My comment: The current name of the city is Shimonoséki. The town is very proud of the fact that the battle of Dan-no-ura was fought nearby, and also of the story Hōichi the Earless. There are sculptures and mention of Hōichi throughout the city. ↩

-

Hearn wrote: The biwa, a kind of four-stringed lute, is chiefly used in musical recitative. Formerly the professional minstrels who recited the Heiké-Monogatari, and other tragical histories, were called biwa-hōshi, or “lute-priests.” The origin of this appellation is not clear; but it is possible that it may have been suggested by the fact that “lute-priests” as well as blind shampooers, had their heads shaven, like Buddhist priests. The biwa is played with a kind of plectrum, called bachi, usually made of horn.

My comment: It may be a strange sound the first time you hear it, but it grows on you. It’s a very pleasant and very Japanese sound. If you’ve never heard it before, here is a good sample.

The biwa hōshi played all kinds of things, but they became primarily known for their retelling of the Heiké Monogatari and were considered the caretakers of that epic tale. See this video for more details. ↩

-

I’m not sure why Hearn decided to give both English and Japanese here, but he does this sometimes in his writing. I don’t have access to the original text that he used for his translation, but Kijin, probably is 鬼神 which translates to demon god or fierce god. What we think of goblins in English would probably better match up with the dangerous Japanese spirit Tengu, which you sometimes see translated as “Japanese goblins” or “Asian goblins”.

Hearn’s grandson, Toki Koizumi, wrote that his grandfather never learned much Japanese and relied on his wife for communication. With that in mind, maybe when Hearn adds Japanese words in brackets or footnotes it is because he isn’t entirely sure of the translation. ↩

-

A response to show that one has heard and is listening attentively. (digitizer note) ↩

-

Daimyō were area lords in feudal Japan. A modern comparison might be a governer. In fact, after the Meiji Restoration, many daimyō became prefecture governers. ↩

-

Hearn wrote: A respectful term, signifying the opening of a gate. It was used by samurai when calling to the guards on duty at a lord’s gate for admission.

My comment: His wife, Setsuko Koizumi, later recalled: “He [Hearn] thought that ‘Mon o aké’ (Open the door) was not an emphatic enough expression for a samurai, and he made it ‘Kaimon.’ (This latter word means ‘Open the door,’ like the former, but would be more fitting in the speaker’s mouth.)” His grandson, Toki Koizumi, also told the same story.

In otherwords, in Hearn’s view the common Japanese expression mon o ake 門を開ける would be too weak coming from a samurai who should instead use the stronger, and the more aristocratic sounding, Sino-Japanese Kaimon 開門. ↩

-

Hearn wrote: Or the phrase might be rendered, “for the pity of that part is the deepest.” The Japanese word for pity in the original text is "awaré.

My comment: Aware (哀れ) was a Heian period expression of measured surprise (similar to “ah” or “oh”). “Pity”, as Hearn says (or “sorrow”), but also “deep feeling”, “sensitivity”, or “awareness”. ↩

-

As previously mentioned, Emperor Antoku was held on that leap of death by his grandmother, The Lady Tokiko (Taira no Tokiko 平時子). Nii no Ama (二位尼) (meaning “Nun of the Second Rank”) is her Buddhist name. She took the sacred sword, Kusanagi, with her on her death leap. The Imperial house claims it was later recovered, but many others say it was lost forever. ↩

-

If you want an idea of what Hōichi was singing, here is a fantastic preformance of Dan-no-ura by Junko Ueda ↩

-

Hearn wrote: “Traveling incognito” is at least the meaning of the original phrase,—“making a disguised august-journey” (shinobi no go-ryokō). ↩

-

This is likely not the same as what was there in the past, but here is Antoku-tennō’s current tombstone: ↩

-

Hearn wrote: The Smaller Pragñā-Pāramitā-Hridaya-Sūtra is thus called in Japanese. Both the smaller and larger sūtras called Pragña-Pāramitā (“Transcendent Wisdom”) have been translated by the late Professor Max Müller, and can be found in volume xlix. of the Sacred Books of the East (“Buddhist Mahāyanā Sūtras”).—Apropos of the magical use of the text, as described in this story, it is worth remarking that the subject of the sutra is the Doctrine of the Emptiness of Forms,—that is to say, of the unreal character of all phenomena or noumena… “Form is emptiness; and emptiness is form. Emptiness is not different from form; form is not different from emptiness. What is form—that is emptiness. What is emptiness—that is form… Perception, name, concept, and knowledge, are also emptiness… There is no eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, and mind… But when the envelopment of consciousness has been annihilated, then he [the seeker] becomes free from all fear, and beyond the reach of change, enjoying final Nirvāṇa.”

My comment: These days we call this sūtra the Heart Sūtra. It is the most famous and popular sūtra in Mahāyanā Buddhism and is considered by many Buddhists to be the best summery of Buddhism itself. You can read Professor Müller’s translation mentioned by Hearn here; or a more modern translation by Thich Nhat Hanh. Just for kicks, you can also hear what it sounds like when chanted in Japanese.

The Heart sūtra is commonly used in East Asian ghost stories as a device to exorcise ghosts or other evil spirits. ↩