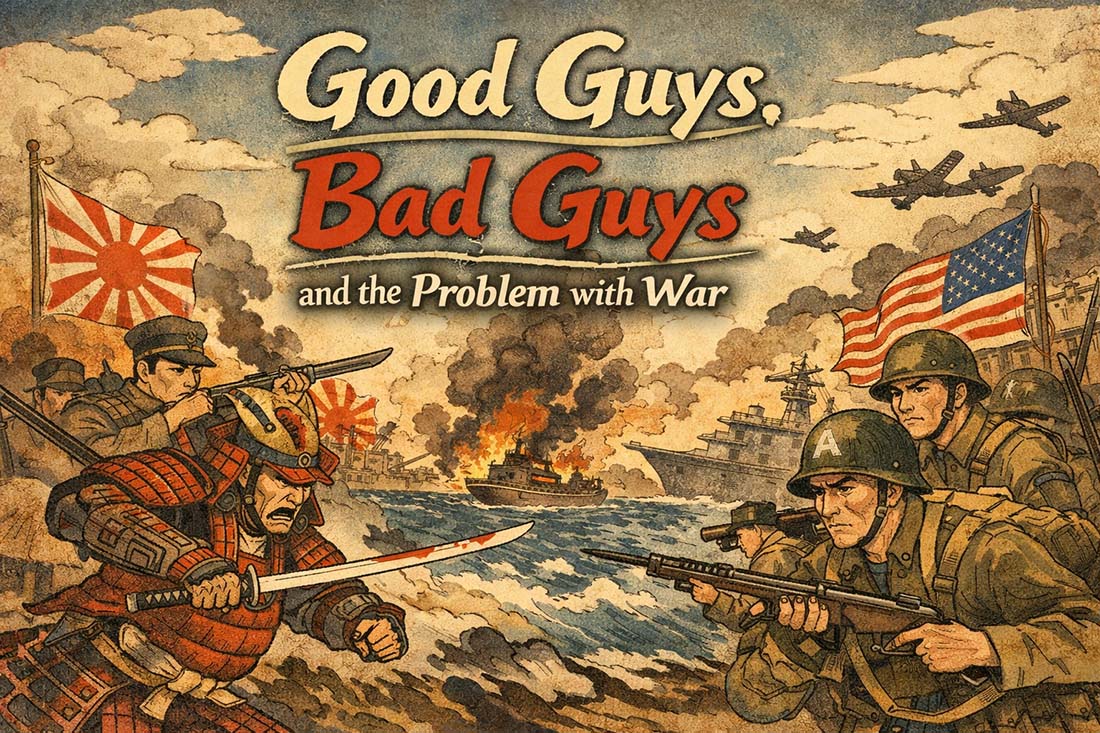

So the other day my oldest asked me about World War II. He asked me if Japan was the bad guy in the war.

Oh man.

Now if you know me, you know I am anti-war. I detest even the very idea of war. Furthermore, I dislike nationalism and am deeply suspicious of patriotism, because it so easily plants the seeds of nationalism. I am not a fan of the Pledge of Allegiance in America for this very reason. It is, quite literally, a pledge of fealty to the state. That has always made me uneasy.

Did you know that originally children in America recited the pledge while performing what looks very much like a Seig Heil?

This was called the Bellamy salute. It predates Nazism, but the resemblance is uncomfortable. Once the Nazis became the obvious villains, the United States quietly changed the gesture to a hand over the heart. But the underlying idea — swearing loyalty to the State — never really changed, even if the gesture did.

So yes, I am often critical of America. But I am critical of every country, including Japan. Bad actions are bad actions no matter who commits them, and they should be acknowledged honestly, not excused or buried just because “our side” did them.

And this is part of why I’m uneasy about patriotic ritual.

I told him simply, “Everyone loses in war, and all sides do bad things.” I don’t know why I expected that to satisfy him. Of course it didn’t.

He followed up by asking if it was true that Japan bombed Hawaii. I said it was. He asked if that made Japan the bad guys.

He is Japanese. And he is American. I don’t want him to internalize the idea that one part of himself is somehow shameful or evil. But more importantly, I don’t think history actually works that way. The world is not black and white, and war especially is almost always very grey.

So I said, “What Japan did was terrible. But it didn’t happen in isolation. America had cut Japan off from oil.”

That led to the obvious next question: “So does that make America the bad guys?”

Kids want simple answers. At his age, a truly complex answer would either bore him or fly right past him. But I can at least try to point him toward the idea that history is a chain of causes and reactions, not a morality play with heroes and villains.

I explained that the oil embargo was a response to Japan’s invasion of China. You can guess what came next.

“If Japan invaded China, were they the bad guys?”

That led further back, to how Japan’s militarism didn’t appear out of nowhere, that it was shaped by Western imperialism, by being forcibly opened by American warships a century earlier, and by a desperate attempt to avoid being colonized itself. Everything has roots. Everything has context. Nothing happens in isolation. (I’ve written more about this elsewhere, see my post Perry’s Black Ships and the Opening of Japan.)[1]

We stopped there. He seemed satisfied with the idea that both sides did terrible things, that neither side was innocent, and that calling one “the bad guys” misses something important. Before we ended the conversation, I emphasized one thing above all else: war is always terrible, and no one truly wins.

The cynical part of me wanted to add, “except politicians and corporations,” but I held back. He doesn’t need that layer yet.

Maybe it was a good conversation. I don’t want to tell him what to think. But I do hope I can help guide him toward understanding that the world isn’t simple, history isn’t clean, and war — no matter the flag — is always a tragedy.

-

I guess I never got around to posting that one here. This is at my Hive blog, where I post more rough drafts and explore ideas that eventually make their way here in a more complete form. ↩