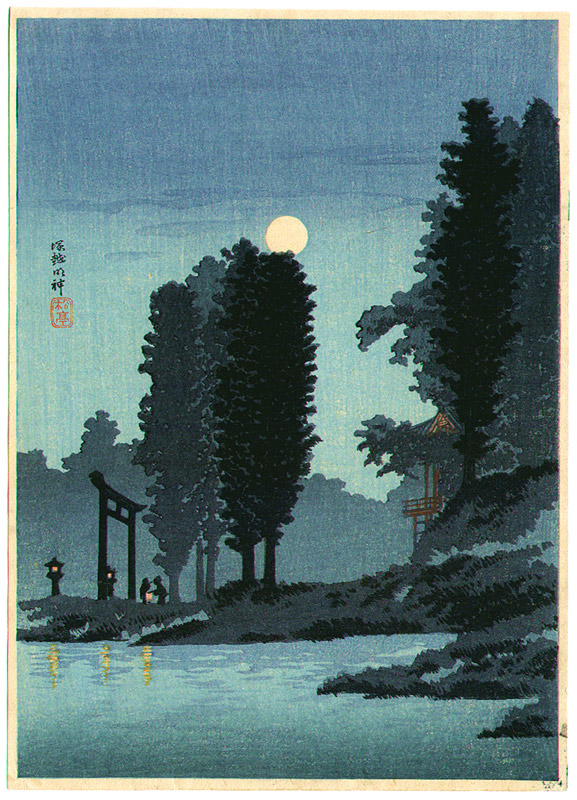

The fall of the Tokugawa Shogunate in 1868 marked a significant shift in Japan’s history, transitioning from the feudal Edo period to the modern Meiji era. The Tokugawa clan had ruled Japan since 1603 but their time was now over, as world events moved against them. Amidst this historical upheaval, a legend was born: the legend of the Tokugawa gold. Rumored to be six chests full of gold hidden in the mountains of Gunma, this tale has captivated treasure hunters and history enthusiasts alike. But what is the truth behind this legend? Let’s delve into the mystery.

The Legend of the Lost Gold of the Shogun

According to popular lore, as the Tokugawa Shogunate was nearing its end, loyalists fearing the loss of their power and wealth decided to hide their treasures. It’s said that six chests filled with gold were secretly transported and concealed in the dense forests of Gunma Prefecture, a region known for its rugged terrain and natural hot springs. The exact location, however, remained a secret known only to a few. As with the best treasure stories, everyone involved with helping transport and bury the gold was killed, limiting the secret of the gold’s location to only a few men.

Years later, a mysterious document was sent to the grandson of one of the men involved in the operation. The document contained the story of the treasure and also contained detailed directions as to the location, supposedly at Mount Akagi.

The Emperor and the Shogun

When you think of Japan, you probably have an image of the emperor having extreme power prior to WWII. Despite that image, the emperor of Japan has rarely held any power for much of the country’s history. Prior to 1185, powerful families such as the Fujiwara controlled the Imperial family and the emperor from the shadows. Then after that date, the military took over in a secession of military governments, or shogunates. During this time, the emperor was a virtual prisoner of Kyoto. He wasn’t even allowed very much freedom in that city and was required to inform the shogunate and get their permission if he even wanted to leave the imperial palace.

The Tokugawa Shogunate came to power in 1603 when Tokugawa Ieyasu won control of the country at the Battle of Sekigahara. They ruling for over 250 years, accumulated immense wealth. Things were stable and peaceful and despite grumbling from some emperors every now and again, there was no threat to their power. Things changed suddenly, however, In 1852, when US Commodore Matthew Perry sailed into Edo Bay and demanded Japan open ports, both for trade and to allow the US whaling ships to refuel there. This set off a series of shocks that resulted in the enemies of the Tokugawa uniting and using the emperor as a means to overthrow the Shogunate.

Foreseeing the possibility of their fall from power, that is when the chests of gold were supposedly hidden.

Is it possible? As the political climate changed, it’s certainly plausible that some sought to safeguard their assets. However, historical records about the actual movement or hiding of such wealth are scant, leaving much to speculation.

Tokugawa Gold

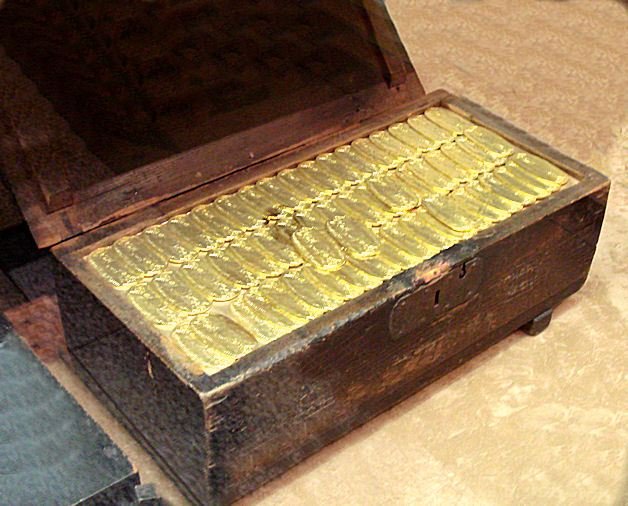

As far as I know, the exact details of the gold were never recorded. It’s likely, however, that a large portion of it is in koban (小判). If you’ve ever watched an samurai dramas or period pieces, you may have seen this.

This ovoid shaped gold piece was one ryō of gold, which was the highest unit of currency at the time. See my posts here and here about the currency system in use at the time.[1] There were few standards for minting coins at the time, so the size and weight of a koban varied, sometimes significantly, but in the Edo era it averaged about 1 to 1.5 monme, which is about 3.75 to 5.63 grams. That is around $245 – $397 of value using today’s gold price.

You can imagine how much money six chests full of koban coins would be! In 1941 a story in the New York Times estimated that the treasure would have been worth ¥2,300,000,000. Now I have no idea how to convert that to 2023 dollars, so I asked ChatGPT. It gave me the value $12.25 billion.

You can see why the idea of this treasure has inspired thousands of treasure hunters in the years since.

Searching for the Treasure

The legend has spurred numerous treasure hunts throughout the years. Adventurers and enthusiasts have scoured Gunma’s landscape, looking for any sign of the lost gold. Yet, despite these efforts, nothing conclusive has been found. The lack of evidence raises questions about the veracity of the tale, but it does little to dampen the enthusiasm of those who continue the search.

The grandson I mentioned immediately went to search for the treasure upon receiving the note telling of it. He searched all his life. In 1934 he claimed to have reached a depth in one location of 220 feet, finding bones and a sword bearing his family crest. This suggested to him and others that the story was true.

Slowly enthusiasm for the search did start to decrease, but then in the 1990s a TV show reintroduced the legend to a new generation when they went in search of the gold. That sparked a boom in treasure hunters searching for it, a boom that hasn’t yet died down.

Cultural Impact

The tale of the Tokugawa gold has become a part of Japanese folklore, inspiring books, movies, and has even appeared in video games. It represents a tantalizing piece of Japan’s rich history, blending facts with fiction. The story is more than just a treasure hunt: it’s a symbol of the intrigue and mystery surrounding the end of a powerful dynasty.

The legend of the Tokugawa gold remains one of Japan’s most intriguing mysteries. Whether fact or fiction, it continues to capture the imagination of people around the world. While the truth behind the legend may never be fully uncovered, it serves as a fascinating window into a pivotal moment in Japanese history and the enduring allure of lost treasures.

-

Those two posts haven’t been republished to this site yet. But rest assured that blog those links take you to is mine. I’ll be updating this post when I republish those posts here. ↩