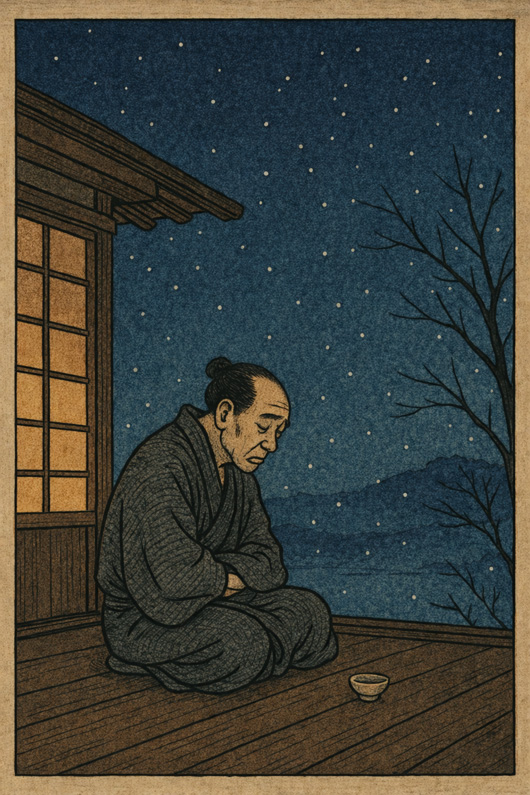

Issa is often remembered for his warmth and humor, but he did have his dark days. This haiku comes from one of these dark periods.

酒呑まぬ吾身一つの夜寒哉

sake nomanu waga mi hitotsu no yozamu kana[1]

no sake to drink —

I’m completely alone

the night is cold…

—Issa[2]

Issa was 31 when he wrote this, and his life at the time was not a happy place. He wasn’t married, was locked in a bitter struggle with his stepmother (who hated him) over his inheritance, had no home of his own, and often had to rely on the kindness of friends or temples for a place to sleep. Many of his haiku from this period are dark or self-mocking.

There is also a bit of nuance in that first line. It’s hard to translate the feeling he’s going for without accidentally suggesting the common refrain of the alcoholic: alcohol is my only friend. 酒呑まぬ literally means “not drinking sake,” but idiomatically it conveys a lack of warmth, company, or comfort. In the Edo period, sake was a small luxury for the poor, and metaphorically it carried associations of warmth in the cold season, conviviality, and a healthy social life. By contrast, its absence could deepen the sense of loneliness. It’s that last that I think he’s going for here.

I don’t have the diary entries around this poem to check his immediate circumstances, but rather than literally talking about rice wine, I lean toward reading the phrase figuratively — as a shorthand for the small comforts that are missing from his life and even more strongly, how much his life sucks. Like I said, he was depressed.

I don’t want to change his words, so “no sake to drink” is the best I can come up with in English, but just be aware that he probably isn’t really talking about sake.