And here is your daily almanac for Sunday, the third of December 2023.

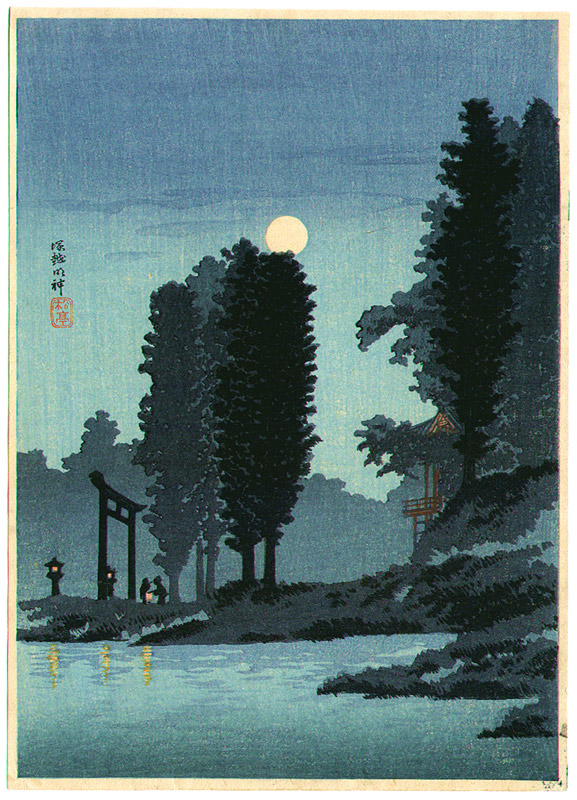

Today, in 1882, Taneda Santōka was born, one of the most beloved Japanese haiku poets, famous for his free-verse haiku, his wanderings across the Japanese countryside, and his love of sake. His haiku are celebrated for their simplicity and profundity, capturing the essence of the moment in a few brief words, often even fewer words than traditional haiku.

Santōka’s life was marked by hardship and spiritual seeking. Tragedy entered his life early when his mother committed suicide by throwing herself into the family well when he was only eleven. He was present when they raised her lifeless body from the well. This incident would haunt him his entire life. He turned to alcohol early to help cope. He was very bright and was accepted into the illustrious Waseda University but was forced to drop out due to his drunkenness. His father, who had once been fairly well-off, was nearly broke by this time, furthering the stress on Santōka.

Despite the troubles with alcohol and depression, he discovered haiku while a student and soon became a disciple of Seisensui, the leading haiku reformist who sought to break from the traditional 5–7–5 syllable requirement and establish a free-form modern haiku format. Santōka embraced this modern idea and became one of Seisensui’s leading disciples.

Financial and mental troubles kept following him, however, and in 1924 at age 42, he attempted to kill himself by jumping in front of a train. He survived and was taken to a nearby Soto Zen temple to recover. At the temple he thrived and soon was ordained. Not long after, he started what he would do for the rest of his life: wandering all over Japan, drinking sake, and writing haiku.

He wandered across Japan, living a life of simplicity and humility. His poetry often reflects these experiences, eschewing traditional haiku structure to express his unencumbered, free-spirited approach to both life and art.

He is my favorite haiku poet and is slowly becoming Japan’s favorite haiku poet as well. There is something about his tragic life and his amazing haiku that makes this drunken wandering Zen haiku poet very likable.

Today’s rokuyō is shakkō (赤口), considered a less auspicious day, especially in the morning. According to belief, it’s a day when extra caution is advised in the early hours. (Read more about the rokuyō here)[1]

On the old calendar, today would have been the twenty-first day of the tenth month. We are in the midst of Shōsetsu (小雪), the time of early snow, and the microseason Tachibana hajime te kibamu (橘始黄), when tachibana (Japanese bitter oranges) begin to turn yellow. This is a time when nature slowly shifts its colors, reminding us of the cycle of life and the impermanence that Santōka so beautifully captured in his haiku.

Here’s a haiku from Santōka:

また見ることもない山が遠ざかる

mata miru koto mo nai yama ga tōzakaru[2]

mountains I’ll never see again

fading away behind me[3]

—Santōka

There is a lovely acceptance here. He knows or guesses that he’ll never make this same journey again and will never again see these particular mountains. I think this haiku sums up Santōka well, showing his ability to find meaning in every step and to see the profound in the ordinary. As the mountains fade, so too do moments in our lives, leaving behind a trail of memories and experiences that shape who we are.

Santōka’s life, filled with both hardship and beauty, resonates in these words. His recognition of the impermanence of life and the constant change inherent in existence is a theme that is deeply rooted in Buddhist philosophy and is vividly expressed in his poetry.

As we remember Santōka and his journey, this haiku invites us to embrace the fleeting nature of our experiences, to appreciate the beauty of the present, and to acknowledge the constant ebb and flow of life.

As we experience the early signs of winter and observe the changing hues of nature, let us reflect on Santōka’s journey and find our own paths through his words. Let’s appreciate the moment, the journey, and the simple beauty around us. Be well, do good work, and stay in touch.

-

Like many things on this site, I haven’t restored the version I made for this website yet and this is a lesser version I wrote for my Hive blog sometime ago. I will try to remember to update this whenever I repost the article on this site. ↩