Even in his moments of forgetfulness, Issa finds poetry, turning a lapse of memory into a moment of laughter and quiet insight.

うかと来て我をかがしの替哉 一茶

uka to kite ore wo kagashi no kawari kana[1]

absent-minded

I’m the scarecrow’s

replacement

—Issa[2]

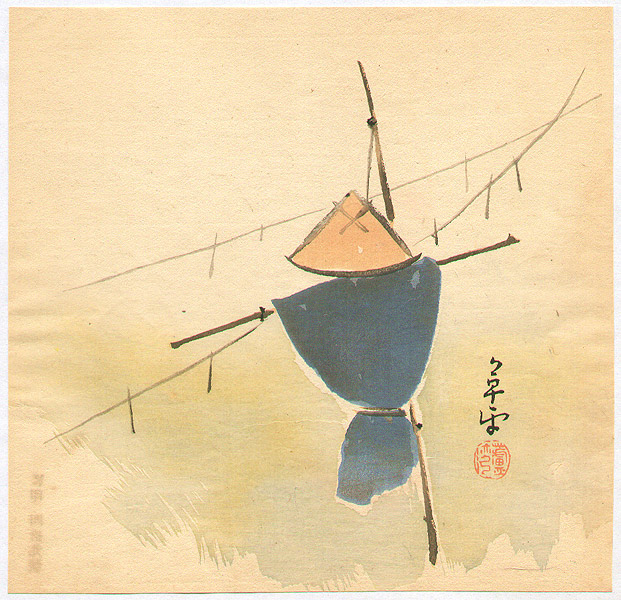

This is a fun haiku from Issa showing his characteristic blend of humor and humility. Written in 1814, it imagines the poet standing absent-mindedly, presumably upon moving somewhere and forgetting why he wanted to be there, so still and unfocused that someone might mistake him for a scarecrow. It is comic and strangely touching, a flash of human self-awareness that turns a moment of distraction into poetry.

Issa returned to this idea a few years later, writing in 1818:

ふいと立おれをかがしの替哉

fui to tatsu ore o kagashi no kawari kana

suddenly I’m

standing, mind gone —

their new scarecrow

In the later version, his humor sharpens. The mood shifts from “I was mistaken for a scarecrow” to “I’ve become one,” as if his absentmindedness has completed the transformation. It’s this gentle self-deprecation humor that makes Issa so relatable even two centuries later.

We’ve all had moments like this: you stand up to do something, only to forget why. You wander into another room, your purpose dissolving somewhere between steps. There’s a moment of blankness, of suspension. ….why did I come in this room, we think to ourselves. In Issa’s world, that tiny lapse becomes a glimpse of life’s absurdity.

It’s tempting to read these haiku through the lens of aging—memory lapses, distraction, but they also speak to a universal, timeless kind of inattention. The mind drifts; the body remains. Issa, ever the observer of small, ordinary moments, turns even forgetfulness into art.

What makes his humor endure is its warmth. He never mocks others, only himself — and even then, gently. It perfectly captures the essence of Issa’s personality: tender toward all living things, yet aware of his own ridiculousness. It’s self-mockery as compassion.

There’s also a quiet philosophical thread here. A scarecrow is an imitation of life: a man-shaped thing that fools birds. In mistaking himself for one, Issa acknowledges how thin the line can be between life and its semblance, between purpose and pause. His moment of blankness becomes a kind of Buddhist stillness: the ego fading, awareness merging with the field, until all that’s left is form and silence.

That could be a stretch. But Issa was quite serious in his Buddhism, so I don’t think it is.

At any rate, we might laugh, but we also recognize the feeling. That moment of standing there, thoughtless, caught between doing and being. The thing is, it’s not just forgetfulness. It’s a tiny enlightenment, however unintentional. So there you go: next time you forget why you entered a room and your kids or spouse laugh at you, just smile and tell them you are searching for enlightenment.